|

Thinking inside the box: designing information

for homeless drug injectors

Lifeline is best known, damned and praised for its publications. They have always been produced with a design process that starts with talking to the target audience and then carries on talking to them right through to the end product. Mike Linnell describes Lifeline’s latest and no less controversial initiative.

On the

face of it, giving a homeless heroin user a leaflet, seems about

as useful as giving a cookery book to a famine victim. What we embarked

upon was a design project in the broadest and truest sense of the

word. An example of ‘good’ design is the clockwork radio: it was

designed to solve a problem for people from the developing world

without access to electricity or the means to afford batteries for

their radios. Its design was ‘good’ not because it looked ‘cool’,

but because it solved the problem it set out to address. On the

face of it, giving a homeless heroin user a leaflet, seems about

as useful as giving a cookery book to a famine victim. What we embarked

upon was a design project in the broadest and truest sense of the

word. An example of ‘good’ design is the clockwork radio: it was

designed to solve a problem for people from the developing world

without access to electricity or the means to afford batteries for

their radios. Its design was ‘good’ not because it looked ‘cool’,

but because it solved the problem it set out to address.

Identifying the problem to be solved

Through contacts we built up a picture of the homeless target

audience in general and eventually decided to concentrate on ‘homeless

heroin injectors’ as their problems seemed most acute and were the

most drugs-specific group.

A mixture of individual and group interviews was used. They were asked about themselves, their daily life and their drug use and were also asked about what information they wanted, in what format, how well they could read and so on.

The research identified a number of problems, for example about injecting techniques. This meant getting detailed observation and demonstrations of technique from users. Injecting yourself in the groin while standing up (the Japanese bow) in a public toilet requires some practice. Some problems were unresolvable: the possibility of injection rooms was taken up with the Chief Constable of Greater Manchester Police before being rejected. So we focussed on those issues that we could realistically tackle.

Problem : overdose.

Overdose among this group was common, particularly those who had

recently been released from prison. In Greater Manchester ringing

for an ambulance was problematic because the police were automatically

called to the scene. Many of the ‘homeless heroin users’ had outstanding

warrants or were using aliases; the last thing they wanted was any

further contact with the police. The usual procedure was for others

to leave them in a phone box or drag them into the street (usually

after relieving them of any drugs or money they had on them).

“Me and four mates of mine have got this pact that if any of us go over (overdose) we’ll leave him there, they put me in a phone box and ring for an ambulance. I don’t want them paying for my silliness, I don’t want them going to jail”.

Solution : policy and publicity.

We

produced an overdose guide using few if any words. For this guide

to work the delay in ringing for an ambulance had to be kept to

a minimum. A scheme had been piloted by the East Midlands Ambulance

Service whereby with the exception of death, childcare issues or

violence towards staff, the police would not be called to the scene

of an overdose. We worked with Greater Manchester Ambulance Service

and Greater Manchester Police to adopt a similar policy that was

implemented in January 2002. We

produced an overdose guide using few if any words. For this guide

to work the delay in ringing for an ambulance had to be kept to

a minimum. A scheme had been piloted by the East Midlands Ambulance

Service whereby with the exception of death, childcare issues or

violence towards staff, the police would not be called to the scene

of an overdose. We worked with Greater Manchester Ambulance Service

and Greater Manchester Police to adopt a similar policy that was

implemented in January 2002.

While a number of guides illustrate basic first aid, the paramedics

we spoke to felt in reality it was difficult remembering this in

an emergency and so better to demonstrate and teach the techniques.

The Ambulance service anecdotally reported that a lot of the 1100

heroin overdoses they dealt with in the area involved recently released

prisoners (backed up by the ACMD report into drug related deaths).

So a guide for recently released prisoners featuring overdose information

was also produced. Finally, the local DATs were able to fund the

secondment of a paramedic to initiate a programme of training. When

this was all in place we did a press launch involving all the services,

as the policy would be useless unless drug users were aware of them.

This achieved considerable local coverage without any adverse publicity

for the Police or Ambulance services. The main guide could now be

produced with some hope of achieving its aim.

Problem 2: injection.

Poor injection technique was a major concern and had resulted in serious damage/ limb loss. Users existing knowledge was gained from a variety of sources; usually they were injected by other people and then learnt by a process of trial and error. Injecting in the groin was common, either through a lack of useable surface veins; a belief you got a better hit or to hide injection marks from homeless hostels or family. Injecting occurred in various locations; in friends’ houses, in toilets, or in make shift ‘shooting galleries’. It would be hard to imagine a place less suited for the preparation and injection of heroin

Solution 2: the box.

The first solution we came up with was a graphic (in both senses) injection guide that could be understood by those with reading difficulties. At every stage of this design both the users and our design panel were consulted. The basic guide uses a standard technique of injecting in the arms, and another guide considered problems that arise from injecting. To supplement this we have two other guides: one for those that are already injecting in the groin and a detailed guide to smoking heroin. The smoking guide is designed both for heroin users on release from prison (some heroin users we encountered did not know how to smoke heroin) and for those injectors who want to stop injecting as recent research has shown that smoking heroin may be a viable alternative for some.

To solve the problems of discarded needles and the unhygienic environment we came up the idea of a cardboard box for the works to fit in. The box itself opens up to become the ‘clean space’ for preparing heroin. This was originally an Australian idea where injectors are encouraged to prepare heroin on a magazine. Anything that you use for injection stays in the clean space; nobody else’s equipment enters your clean space. The box is like a miniature pizza box; we tested this until we found one small enough to carry around but with a big enough area to cook up on. Wordless instructions inside the box showed how to use it.

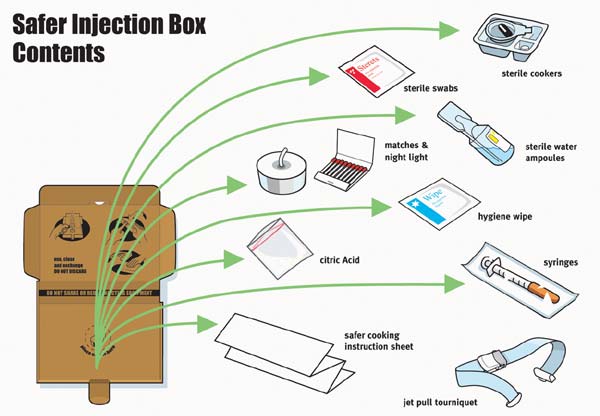

Apart from the guide, the box contains enough injection paraphernalia

for a days use, much of this already available from our needle exchange;

needles, swabs, filters, water, and citric acid. We also added hand

wipes, a tea light for cooking, matches, disposable cookers and

a quality tourniquet. The contents of the box were subject to the

same process as everything else, in that we tried them out with

the target group and ‘experts’ from a variety of disciplines such

as infection control specialists.

The box is designed for a very specific group (those that inject

in the city centre); it is intended to be a one-for-one exchange

on a daily basis. We looked at the possibility of using video cassette

cases, which are as strong as sharps, but discarded this as it was

a) more likely to be used for longer than a day and b) they were

far more expensive. Expense is a major consideration if this initiative

is to be adopted, as needle exchange budgets are finite. Needles

and a sharps box are also provided. When the box is finished with,

it could be closed up and disposed of in a large sharps box. On

the outside of the box are biohazard warnings and our phone number.

If the box was dropped on the street, it was preferable to discarded

syringes. The computer programme in our needle exchange will be

used to ensure daily returns by being able to identify those on

the scheme who were not returning the boxes. A practical protocol

was developed by the workers in the needle exchange to ensure this

happened and to deal with those who did not return the boxes. This

did not involve any change in confidentiality policy. If users failed

to return the boxes they would not be denied access to clean equipment,

just the boxes.

To get the boxes (which were seen as highly desirable by users),

they had to come in and see the nurse at Lifeline’s city centre

needle exchange. The nurse would give them a health check and talk

through any problems connected with injection. They would then be

talked through the injection guide (also available in a poster form

for this purpose), so that they fully understood the instructions.

This was a major aim of the box. Like many needle exchanges contact

with clients is often fleeting and can take months to develop beyond

the provision of equipment.

Drug paraphernalia and Section 9a of the Misuse of Drugs Act.

A six-month evaluation of the box was due to start in July, but has been delayed while some issues around the evaluation are resolved. We have been informed by Greater Manchester Police that ‘Lifeline are open to prosecution’ under Section 9a of the Misuse of Drugs Act for giving out the heroin cooker, candle and matches. The Home Office inform us that the Government is currently considering the ACMD’s recommendations that would allow needle exchanges to do what they already do by giving out “sterile water ampoules, swabs, spoons and bowls and citric, but not filters or tourniquets”. Until the government make a decision, the matter is in the hands of the Crown Prosecution Service. This section of the Act was designed to stop the sale of items used in the preparation or use of drugs. It has not deterred Tesco from selling King Size cigarette papers or ‘Head shops’ from selling anything as far as I am aware. At the time of writing Lifeline intend to proceed with the evaluation of the box. Although the Crown Prosecution Service do not generally prosecute because a prosecution would not be in the ‘public interest’ we await the outcome with interest.

Conclusions:

The design process should involve research and problem solving as much as it involves aesthetically pleasing graphics and marketing. Research can often be judged a success by a measurement of academic validity, even if it has no impact on the daily lives of the people it is studying. Graphics can be judged a success by simple looking nice. Design should only be judged a success if it solves the problems it sets out to address and even then it fails unless the design is adopted and affordable (Sir Clive Sinclair thought he was on to a winner with the Sinclair C5).

When Lifeline first produced Smack in the Eye it was seen as groundbreaking. We were criticized and threatened with prosecution, but we carried on as we not only believed we were right, but it was based on a solid theoretical approach to research, design and health education. These days there are many examples of excellent information products for drug users produce by organisations in the UK. Unfortunately we have had comments from the Department of Education and the Home Affairs Select Committee indicating a wish to return to a shock horror approach to drug education/information – and subsequently plenty of adverse criticism of Lifeline in the national press. This retrograde step should be resisted. It is important to produce information products with the same degree of scrutiny, commitment, resources and expertise as anything else we do with drug users.

i In fact the majority were buying and using a mixed deal of heroin and crack cocaine (brown and white) and it would take half a page to simply define ‘homelessness’. They are referred to as “homeless heroin users’ throughout to save time.

ii Behaviour change is incredibly difficult to achieve and measure through mass media techniques. Interpersonal communication (you talk with somebody and they can talk back) is more likely to be successful. The box is designed to moderate behaviour by using mass media techniques to bring about and reinforce interpersonal communication. In other parts of this communication project (young heroin users selling male to male sex) the research itself became part of this interpersonal communication by linking in with service provision.

|